A Brief History of Settler-Colonialism and Indigenous Resistance in Ohio (Part 2)

“The human condition is less illuminated by the situation of privileged humans than by the situation of its oppressed majority, and it is here that we must begin our quest.” -Charles W. Mills, Unwriting and Unwhitening the World (2015)

“Armed with the knowledge of our past, we can with confidence charter a course for our future. Culture is an indispensable weapon in the freedom struggle. We must take hold of it and forge the future with the past.” -Malcolm X, Speech at Founding Rally of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (1964)

“. . .the only way to stop this evil [white settlement of the Indians' land], is for all the red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land as it was at first, and should be now - for it never was divided, but belongs to all. . . .Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds and the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit [Master of Life] make them all for the use of his children?” -Tecumseh in a letter to William Henry Harrison (1810)

In part one of this essay, we briefly surveyed some defining events of settler-colonialism and Indigenous resistance in the Ohio Country. Next, our focus will turn towards Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, and the anti-colonial movement they helped organize against the United States at the turn of the 19th century.

The historical origins and subsequent development of capitalism and ‘whiteness’ were co-constitutive processes- a dynamic, multi-century and global process of ‘how the West came to rule’. Alexander Anievas and Karem Nişancıoğlu argue that the geopolitical origins of capitalism did not have a virgin birth in the English countryside during the sixteenth century, but was instead the outcome of a wide assemblage of inter-imperial rivalries, structural crises, and conjunctural catastrophes. They argue that capitalism’s origins can be traced through a multitude of world-historic events: from the Mongol Empire and the Black Plague during the 13th and 14th centuries, the Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry over the 16th century, and the Trans-Atlantic slave-trade through the 16th to the 19th century; to the Mughal Empire, European (settler)colonialism, the ‘Bourgeois Revolutions’ of Europe, the imperialist partition of Africa, and of course, the decline of feudalism and the rise of the industrial revolution.

Anievas and Nişancıoğlu’s account of the geopolitical origins of capitalism and how the West came to rule provides a very rich tapestry of world history from a non-eurocentric and subaltern point of view. Their non-teleological historical narrative demonstrates that capitalism and ‘whiteness’ were not simply ‘natural’ or pre-determined social phenomena, nor merely the necessary outcomes of human development. Instead, they show that this blood-soaked, multi-century process was one engrossed with social contradictions- a process that did not seamlessly evolve without being contested and resisted at every step of the way.

It is through examining history ‘from the ground-up’- through the dialectical framework of exploiter/exploited, oppressor/oppressed, power/resistance- that we can best grasp the totality of our present circumstances. "Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past." If we are to make our own history, we must first confront and reckon with our present circumstances, ‘given and transmitted from the past’.

For those of us in the so-called “United States”, reckoning with our present circumstances immediately entails confronting the historical legacy and remanence of settler-colonialism. This is especially the case for those of us who reside on the unceded land of the Shawnee, Cherokee, Erie, Wyandot, Miami and other Ohio Valley tribes- present day “Ohio”. Home to the Hopewell Mounds, a collection of Indigenous earthworks and burial sites established by a diverse network of ancient communities who thrived in North America from 200 BC to 500 AD, “Ohio” contains the largest concentration of ancient Indigenous earthworks in the world. These sites identify and signify the real and often forgotten history of ‘the other trail of tears’ and the anti-colonial resistance spearheaded by Indigenous people against the U.S. settler-colonial government.

Focusing on the lives and politics of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa gives us a window into an important historical reality which is all too often forgotten or mystified, if not consciously erased. In our society, the lives, ideas, and politics of Indigenous people during the colonial era are often perceived as archaic relative to our “democratic”, capitalist and industrialized society. The politics of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa cut sharply against this false notion, and demonstrate that they held advanced and far-reaching ideas about an equitable form of social organization and reproduction- a social system which was elaborated and defined in contradistinction to the class-based, settler-colonial society best epitomized by the United States.

The Early Lives of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa

Tecumseh (1768-1813) and Tenskwatawa (1775-1836) were Shawnee brothers. They were two of Shawnee war chief Pucksinwah’s eight children. Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa’s parents, Pucksinwah and Methoataaskee, met in present-day Alabama. Many Shawnee had migrated to Alabama and elsewhere following the Beaver Wars, when the Shawnee were driven out of Ohio Country by the Iroquois.

In 1759, Pucksinwah and Methoataaskee moved back to Ohio Country as part of a larger effort to reunite the Shawnee in their homeland. In 1763, Pucksinwah fought in Pontiac's Rebellion, an inter-tribal military campaign to halt the advance of European settlers into the Ohio River Valley. He later died during the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774.

Tecumseh was born in 1768 in what is present-day Chillicothe, during a somewhat peaceful decade between Pontiac's Rebellion (1763) and the Battle of Point Pleasant (1774). Tecumseh was about seven years old during the outbreak of the American Independence War. Too young to fight at this time, Tecumseh relocated with his family to present-day Springfield, Ohio, to avoid the raids U.S. settlers were carrying out on Shawnee villages.

Tenskwatawa was born early in 1775, shortly after Pucksinwah’s death. Tenskwatawa had a lonely and isolated upbringing. In 1779, due to her depression following Pucksinwah’s death and her fear of the American Independence War, Methoataaskee moved further westward, leaving Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, and their siblings under the care of their older sister, Tecumpeas. Soon thereafter, the Kentucky militia carried out raids on Shawnee villages in the western part of Ohio Country, chasing Tecumseh’s family and their tribe north towards present-day Bellefontaine, Ohio in 1780.

The conditions which animated and impacted Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa’s upbringings greatly shaped their worldviews and politics. They were born into a world of constant terror – from the violent encroachment of the settler-colonists to the instability and dislocation of intercolonial war. Furthermore, they came out of a long line of Shawnee warriors who spearheaded anti-colonial resistance against these forces. This resistance provided a clear model for the struggle to defend their land against the European settlers.

Lessons of the United Indian Nations

Following the close of the American Independence War, and in anticipation of the continued encroachment and terroristic raids by U.S. settlers, Indigenous tribes throughout Ohio Country and the Great Lakes regions convened in Lower Sandusky to host a pan-tribal conference in 1783. At this conference, the United Indian Nations advocated for Indigenous unity in opposition to U.S. colonialism. They elaborated a doctrine of communal ownership of the land by Indigenous people in common, and argued that the U.S.’s quest to exploit and profit off of their land, resources, and people was irreconcilable to their communal principles.

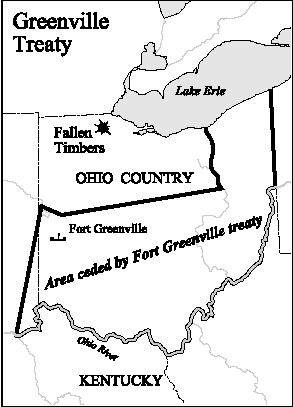

The ideas elaborated at the 1783 conference profoundly moved a 15-year old Tecumseh, who was in attendance. He channeled the communalist, anti-colonial, and pan-tribalist ideas he encountered there – forcefully enough that many confused him as the originator of these ideas. Both Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa would later become critical of the United Indian Nation’s leadership, after they signed away many concessions in the Treaty of Greenville following the Northwest Indian Wars.

Over the course of the decade following the American Independence War, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa would embark on different paths, although they would ultimately end up with an identical political goal: the destruction of the U.S. settler-colonial state. To do so, they both agreed it was fundamental that Native leaders should under no circumstance collaborate or make any conciliations with the United States.

Tecumseh would go on to become a notable and battle-hardened warrior, participating in over forty counter-assaults against settlers traveling down the Ohio River; as well as fighting within the ranks of Blue Jacket and the United Indian Nations during the Northwest Indian Wars, and fighting at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. By the turn of the 19th century, Tecumseh had been a committed and active anti-colonial militant since his adolescence, and he had become a highly admired war hero and political leader among the Shawnee.

Tenskwatawa, on the other hand, struggled with alcoholism, depression, and anxiety during his young adult life. Differently from his brothers and father, Tenskwatawa wasn’t so much a notable warrior, and instead practiced medicine as a way of participating in tribal life. However, his alcoholism and depression would only deepen as he struggled to treat the European-origin epidemics ravaging Native communities. By the turn of the 19th century, Tenskwatawa had developed a reputation for his alcoholism within his community, which he seriously struggled with until his late twenties.

Tenskwatawa’s Political-Turn (1805)

Beginning in 1805, Tenskwatawa underwent a period of enlightenment and spiritual awakening. Following a near-death experience from alcohol poisoning, Tenskwatawa began elaborating and advancing a religious and philosophical doctrine which earned him a reputation as “the Prophet.” Tenskwatawa advocated a way of life for Native people based on complete separation from European colonialism – including drinking alcohol, dressing like white people, practicing Christianity, and trading with colonial settlements. Tenskwatawa argued that in order to live an honorable life and to reach the afterlife, Native people must struggle against the U.S. settler-colonial state which he identified as the root cause of all the turmoil which had enveloped Native life.

Tenskwatawa’s new reputation as a religious and intellectual leader among Native people posed a serious threat to the colonial ruling-class. The Prophet had developed quite a powerful movement behind his ideas, attracting thousands of Native people eager to hear his lectures. Tenskwatawa’s ideas were dangerous to the U.S.’s settler-colonial project because they aimed to rupture the collaborationist and conciliatory relations some tribal leaders had established with the U.S. at that time, such as the Treaty of Greenville signed by the leaders of the United Indian Nations in 1795. The Prophet’s doctrine also advocated unity among all Native tribes and a return to more traditional ways of living prior to the onset of European colonization.

Tenskwatawa’s anti-colonial political-turn, along with his new-found popularity as a religious leader, laid the basis for a common political project with his brother, Tecumseh. Unlike Tenskwatawa whose anti-colonial activities were primarily directed towards the realm of religious ideas and asceticism, Tecumseh’s anti-colonial practice was directed towards the art of war, military strategy, and building a united front among the Indigenous against the U.S. settler-colonial state.

By the time of Tenskwatawa’s political awakening, Tecumseh had already developed a small group of followers, most of whom were warriors dissatisfied with the discredited leadership of the United Indian Nations. Tecumseh’s detachment was a well-organized and disciplined group which traveled throughout North America to recruit other tribes to the cause of fighting the United States. Tecumseh and his followers argued that the Treaty of Greenville and all other U.S. treaties were worthless and they refused to recognize them. A selection of Tecumseh’s followers were tasked with returning to their villages in order to win leadership and influence away from some of the more conciliatory tribal leaders.

Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa Combine Forces at Greenville (1805)

Despite their different approaches, both Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa shared a common hatred for the United States as well as an understanding of the inherent nature of settler-colonialism: its class-basis and it’s expansionist, exploitative and genocidal tendencies – along with it’s parasitic and irreconcilable relation to Native societies.

In 1805, the two brothers moved to Greenville, Ohio to begin working together. Greenville during this time laid just East of the boundary line established by the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. The location where they began their movement was itself a provocation – it lay within territory claimed by the United States. As word spread that the Prophet and “the Prophet’s brother” were headquartering their movement in Greenville, other Native militants from a variety of other tribes began to join them there.

The U.S. government also caught word of the Shawnee brothers’ movement and attempted to expel them from the “State of Ohio”. After signing the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the U.S. slave-owner Thomas Jefferson was eager to expand the borders of the U.S. westward past the Northwest Territory to the Rocky Mountains. However, the anti-colonial resistance spearheaded in Greenville posed a serious threat to Jefferson’s colonial aspirations. The U.S. proved incapable of convincing land speculators and small farmers that it was safe to build settlements in the region as long as Tecumseh’s followers were launching raids on settlers- killing farmers and their families.

Under orders from Thomas Jefferson, the Governor of “Ohio”, Edward Tiffin, was tasked with quelling the Greenville resistance. Through a series of treaty negotiations with tribal leaders of the region, the U.S. attempted to formalize their theft of the Native’s land. Tecumseh used these meetings to denounce, delegitimize, and demoralize U.S. officials during public speeches, declaring that their “treaties” were worthless, further convincing them that they would be incapable of expelling their movement from the region without engaging in armed struggle. Tecumseh’s forceful speeches during these meetings further inspired his followers, as well as recruiting more to break away from tribal leaders that collaborated with the U.S. during treaty negotiations.

During their time in Greenville, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa successfully consolidated disparate groups of Native militants into a common anti-colonial project with shared political principles. The radicalism of their movement posed as a forceful example to those of the Indigenous population who had become demoralized and disaffected by the forces of U.S. settler-colonialism and felt powerless in resisting it. What’s more, their movement posed a serious threat to the very foundations of the U.S. project – contesting and bringing into question its ability to expand its colonial conquest further westward as envisioned by the Continental (slave-owners’) Congress.

Ultimately however, the residual effects of settler-colonialism in the region, in combination with the sizable growth of their movement forced Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa to move away from Greenville in 1808. The surrounding forests had been depleted of vital resources required to sustain the movement there. Consequently, they opted to move westward to a more fertile location that could sustain an encampment of its size which was quickly expanding.

The Founding of Prophetstown (1808)

By invitation from the Potawatomi, Tenskwatawa, Tecumseh, and their followers moved approximately 150 miles west from Greenville to a location along the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers in Indiana Country (near present-day Lafayette, Indiana). At this new site, there was an abundance of hunting grounds to sustain the village's means of subsistence, as well as no presence of settlers in the immediate area. Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh were satisfied with their organization’s new location, and began to envision new possibilities for the development and furtherance of their movement.

They named it “Prophetstown”. At its height, Prophetstown would grow to be nearly two-miles long, serving as a training ground for nearly 3,000 Native militants who joined the movement, and representing fourteen different Tribes.

During the initial phases of Prophetstown construction and growth, Tecumseh travelled throughout Ohio Country and the Great Lakes Region in an attempt to reconnect with tribes of the region and persuade them to join the Native resistance in Indiana Country. Tecumseh recruited a handful of militants during this time, but his trip was not without tribulations. Some tribal leaders were demobilized and jaded by the effects of centuries of settler-colonial terror; whereas others were skeptical of Tenskwatawa’s doctrines. Without abandoning their struggle, Tecumseh began to question if Tenskwatawa’s religious zeal might impede its advance.

Upon returning to Prophetstown, Tecumseh discovered that the city was beset by the same hardships they had faced in Greenville – food shortages and the spread of disease. Hunger and illness in Prophetstown weakened the movement at the most crucial moment. Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa’s vision of making Prophetstown into the capital city of their united Indigenous nation was in tatters and on the verge of collapse in its infancy.

Despite these complications, the anti-colonial movement at Prophetstown at its height, and its members were still committed to organizing and launching a rebellion against the U.S. and the establishment of their own, independent nation. Time was of the essence, so Tecumseh set out on a trip throughout North America to assemble the forces required to mount their rebellion, this time going West and South.

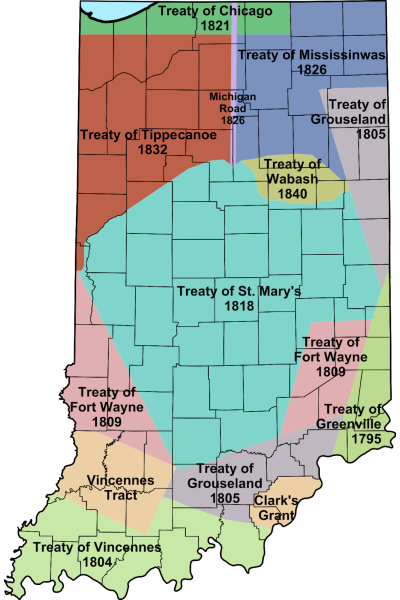

Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809)

While Tecumseh was away from Prophetstown gathering forces to join the Ohio Valley Confederacy, William Henry Harrison assembled a council of Native leaders for treaty negotiations in the Fall of 1809. At these negotiations, Harrison offered large sums of money in exchange for the Native leaders’ cooperation, and purposely excluded tribes who would have been principally opposed to such deliberations – such as the Shawnee – and instead opted to only invite those leaders partial to conciliation. Harrison and the U.S. government were becoming increasingly conscious of and worried about the Ohio Valley Confederacy’s activity and used the Treaty of Fort Wayne as a preemptive maneuver in anticipation of imminent armed struggle with the Confederacy. The treaty ceded nearly 3,000,000 acres of land along the Wabash River to the United States.

Upon hearing about the signing of the Treaty, Tecumseh gathered 400 armed warriors to confront Harrison and demand that he nullify the treaty. At that meeting, Tecumseh argued that tribal leaders did not have the right to sell Native land, because the land was owned by no specific tribe but instead was owned by all Natives in common. Tecumseh claimed that the Treaty was illegitimate, and made a vow to oppose any and all tribal leaders who cooperated with the treaty negotiations. The exchange between Tecumseh and Harrison was a heated one, leading to both the men brandishing their weapons at each other during the argument. The Treaty of Fort Wayne was a tipping point in the conflict between the Prophetstown movement and the encroaching U.S. government. If he wasn’t already, Tecumseh was on the warpath. The Treaty of Fort Wayne would lead to Tecumseh’s Rebellion later that same year.

The Battle of Tippecanoe (1811)

With the rising tension between the Prophetstown movement and the U.S., war was inevitable. In 1811, Harrison marched with an army of 1,000 to the outskirts of Prophetstown with the aim of intimidating them to surrender peaceably, but were authorized to attack the city if necessary. Tenskwatawa, understanding the gravity of the situation, ordered a pre-emptive attack on Harrison’s army in the early morning of November 6th with a war party 0f 500, with the aim of assassinating Harrison during the assault.

Disastrously, the Native-led assault was unsuccessful, as Harrison’s army was able to drive Tenskwatawa’s warriors into retreat. The defeat suffered by the Prophetstown movement at the Battle of Tippecanoe was devastating, demoralizing the city’s inhabitants – most of whom abandoned the city following the battle. The next day, Harrison’s troops arrived at the deserted city and burned the village to the ground. Then he ordered the destruction of Native burial sites. Although Prophetstown had been destroyed, it was not a total defeat for the pan-indigenous movement since many tribes still pledged loyalty to Tecumseh all throughout the country. In fact, it was a relatively small battle. William Henry Harrison, who had done nothing more than defeat a small band of Indigenous insurgents, would become a national hero for his colonizing campaigns in the Ohio and Illinois Countries.

Tecumseh’s Rebellion and the War of 1812 (1811-1815)

The War of 1812 has traditionally been depicted by bourgeois historians as a war of survival for the infant United States against English aggressors. In reality – like the American Independence War – it was a war fought in the interests of colonial expansion. In the case of the War or 1812, this colonial incursion extended into Seminole Florida, Canada, and the rest of the Native territory.

After Thomas Jefferson formalized the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, he proposed to the slave-owners Congress that Native tribes be relocated to reservations. Furthermore Jefferson encouraged the Natives to abandon their traditional forms of production for agriculture and manufacturing. As Howard Zinn notes, “Indian removal was necessary for the opening of the vast American lands to agriculture, to commerce, to markets, to money, to the development of the modern capitalist economy.”

Following the Battle of Tippecanoe, Harrison and the U.S. government believed they had successfully quelled Native resistance in the region. Prophetstown’s defeat at the Battle of Tippecanoe was a serious blow to the Confederacy, although the movement was not ready to lay down its arms. Tecumseh continued to travel throughout North America, attempting to unify disparate Native tribes in the ranks of his Confederacy, hoping to avenge the losses suffered at the Battle of Tippecanoe and the destruction of Prophetstown. In a letter to the U.S. War Department, Harrison noted the incredible speed and distance Tecumseh would travel on his recruitment missions:

"For four years he has been in constant motion. You see him today on the Wabash, and in a short time hear of him on the shores of Lake Erie or Michigan, or on the banks of the Mississippi. And wherever he goes he makes an impression favorable to his purpose. He is now upon the last round to put a finishing stroke on his work."

In 1811, Tecumseh organized a meeting of 5,000 along the Tallapoosa River in Alabama, proclaiming to his audience: “Let the white race perish. They seize your land; they corrupt your women, they trample on the ashes of your dead! Back whence they came, upon a trail of blood, they must be driven.” The Creeks, who lived in present-day Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, were divided among themselves on how to handle the settlers. The Red Sticks, who insisted on protecting their land and culture, would take the side of Tecumseh.

However, many of the tribes Tecumseh visited pushed back against his invitations, such as the Choctaw, Cherokee, and Creek. Those tribes argued that the treaties established with the U.S. government were lawful, and opted to abide by their mandates. This infuriated Tecumseh, who famously retorted:

"Where today are the Pequot? Where are the Narragansett, the Mochican, the Pocanet, and other powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man, as snow before the summer sun ... Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws ... Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves turned into plowed fields?"

With the outbreak of the War of 1812, Tecumseh and his pan-indigenous army would ally with the British, utilizing their weapons and ammunition in assaults against the United States. In the spring of 1813, Tecumseh returned to Canada with an army of 3,000 recruits. In collaboration with the British Colonel Henry Proctor, Tecumseh led a contingent of Native warriors and British soldiers Southward to launch a surprise attack on Harrison and the U.S. Army. At Fort Meigs along the Maumee River in Ohio, Tecumseh’s contingent launched a devastating attack on the U.S. detachment, killing 500 of Harrison’s troops – avenging the burning of Prophetstown.

However, the victory at Fort Meigs would be short-lived. The British command, in response to the growing presence of U.S. troops in the region, would gradually retreat back to Canada. With the growing demoralization and lackluster resolve on the part of the British, Tecumseh felt his vision of a United Indian Nation slipping away. When their band of warriors and soldiers reached the Thames River, Tecumseh informed Colonel Proctor that he and his warriors would retreat no further, and would remain for one final fight at this location. The evening prior to the anticipated battle, Tecumseh informed his fellow warriors that they were “about to enter into an engagement from which I shall never come out. My body will remain on the field of battle.”

The following morning, Tecumseh strategically positioned an army of 1,000 all along the Thames River Valley – composed of members from the Ottawa, Wyandot, Shawnee, Kickapoo, Winnebago, Potawatomi, and Delaware tribes. Even though the Indigenous and British battalions were outnumbered three to one, they had confidence that Tecusmeh would lead them into victory. During the battle, Tecumseh barked orders to his warriors “like a tiger”, refusing to back down even after being shot multiple times. During some point in the battle, Tecumseh’s voice ceased barking orders. On October 5th, 1813, the Americans had achieved victory at the Battle of Thames. In the process of that battle, Tecumseh had been killed, and with him, his vision of a United Indian Nations died as well.

Conclusion

What are the lessons that revolutionaries today can draw from the politics and philosophy of Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, and the anti-colonial, pan-Indegenous war they waged against the United States?

First and foremost, viewing this period of history from the standpoint of Indigenous resistance offers an important historical corrective to the nature and purpose of the American War of Independence. Popular literature tells us that the 1776 Declaration and subsequent war between the Colonies and the British Crown was over poor political representation, unfair taxation, and other empty moral platitudes about the evils of monarchy and the good of Republican Democracy. In reality, this historical revision covers up the true nature of this period of conflict. The Colonial merchants and political leaders wanted to expedite, accelerate, and widen their mission of settler-colonialism on Shawnee and other Indigenous land, and the British Crown was a fetter on their economic interests. This was not an anti-colonial war for self-determination from autocracy, on the contrary, it was a pro-colonial war for a more developed slavocracy.

This point is especially pertinent when the social-democratic left jumps to the gun every 4th of July to celebrate the supposed significance of the slave-owners war. Despite giving superficial acknowledgement to the actual class-nature of the War, they ultimately debase themselves by defending one of the most grotesque and uninspiring movements of the ruling-class in history. This type of social-chauvinism cloaked as revolutionary appraisal should have no room on the left.

Secondly, this history highlights the significance of the self-organization and political independence of the oppressed and exploited in fighting for their emancipation. In contradistinction to other Indigenous leaders who sought conciliation with US leaders through treaty negotiations, Tecumseh and his followers saw no legitimacy to the treaties, and recognized them as a way to placate Indigenous resistance against the US. Although Tecumseh attended and participated in treaty negotiations with the US and neighboring Indigenous communities, he did not see these negotiations as an end in themselves. Rather, he used these spaces to agitate among fellow Indigenous allies, to recruit them to his movement, and to delegitimize their oppressors in the process.

Finally, Tecumseh’s militancy and fate affirms a truth which the left must reckon with: that there is no exit from US imperialism in particular and capitalism in general without a mass revolutionary struggle – with arms if necessary – of the oppressed against the oppressors. The genocide of indigenous people, slavery, and workers’ exploitation formed the essence of the United States. The centuries long struggle against oppression and exploitation in this country must be the bedrock for our struggle for justice today. The struggle for native liberation will be central to forging a new just order in the ashes of today’s system of oppression.