A Brief History of Settler-Colonialism and Indigenous Resistance in Ohio (Part 1)

June 20th marked an historic day as representatives of the Shawnee returned to their ancestral land at Serpent Mound to reclaim its rightful history and the integrity of their ancestral heritage. The opportunity for the Shawnee to return to Serpent Mound and to teach visitors about the site’s true history and the genocidal dispossession of their people by the U.S. government is significant. In recent decades, the site has become increasingly subject to racist and chauvinistic myths and mistreatment by “new age spiritualists” and radical christian cultists, leading to a group of Indigenous people having to defend the site from chrisitan fundamentalists and “Trump worshipers'' in the winter of 2020.

As committed revolutionaries- as serious people of labor, of the colonized, and of the dispossessed- we have a duty to link the struggle for communism with the struggle for Indigenous liberation, for the politics of Land Back, for the right of return for all Indigenous peoples to their Native land, for reparations, and more. As committed revolutionaries who live in the occupied land of the Shawnee, Cherokee, Erie, Wyandot, Miami and other Ohio Valley tribes, we have a duty to learn the real and often forgotten history of anti-colonial resistance spearheaded by Indigenous people against the U.S. settler-colonial government. At the same time, we must understand that the struggle for Indigenous liberation can not be simply relegated to the confines of “history”, as we must recognize that it is in fact an ongoing and living contemporary struggle.

What follows is a cursory introduction to some of the history and political legacy of Indigenous resistance in Ohio. Through examining the anti-colonial politics of Tecumseh and the Inter-Tribal Confederacy of the Ohio Country, we can gain an advanced understanding of what it takes to effectively combat global empires.

Part one of this essay will provide a brief sketch of the historical development and general characteristics of settler-colonialism in the Ohio Country. Part two will provide an appraisal for the anti-colonial resistance and beliefs put forward by Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, and the Inter-Tribal Confederacy of the Ohio Country.

Ohio Country Prior to Settler-Colonialism

Prior to settler-colonialism by the French, British, and, later, the United States, Ohio Country encompassed the region Northwest of the Appalachian mountains: extending from the Ohio River Valley to the Great Lakes region. Before the Colonial era, Ohio Country was primarily home to (but by no-means limited to) three tribes:

- The Kickapoo who lived around what is present day Toledo;

- The Erie who lived along the region South of Lake Erie;

- The Shawnee who lived South of The Kickapoo and The Erie, extending all the way Southward towards the Ohio River Valley.

Following the growth and solidification of settler-colonialism in the regions East of Ohio Country from the 16th to the 18th centuries, many dispossessed tribes would migrate to and seek refuge in Ohio Country. During the colonial era, Ohio Country would become home to several different Indigenous tribes and clans, all of whom had their own cultures, languages, social organizations, and labor practices. These tribes included but are not limited to: The Delaware, Miami, Ottawa, Seneca, and Wyandot.

The Development of Settler-Colonialism in Ohio Country

“The United States made over 400 treaties with Native American tribes, it broke every single one.” Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970)

Through the course of over two centuries, the encroachment of European settler-colonialism in Ohio Country would come to fruition. From the Beaver Wars (1609-1701) through the American Independence War (1775-1783) and the War of 1812, the consolidation of settler-colonialism in Ohio Country was one consciously grounded in and premised on inter-colonial warfare, Indigenous enslavement, genocide and dispossession, and economic conquest by the slave-owning, mercantilist, and settler classes.

It was within this greater historical context in which Tecumseh grew up in: One of colonial warfare and conquest, alongside Indigenous dispossesion, genocide and resistance. In order to fully understand and appreciate the significance of Tecumseh as a revolutionary figure and the militant anti-colonial movement he was a part of, requires a brief survey of the historical and material dynamics Tecumseh and the Shawnee were responding to:

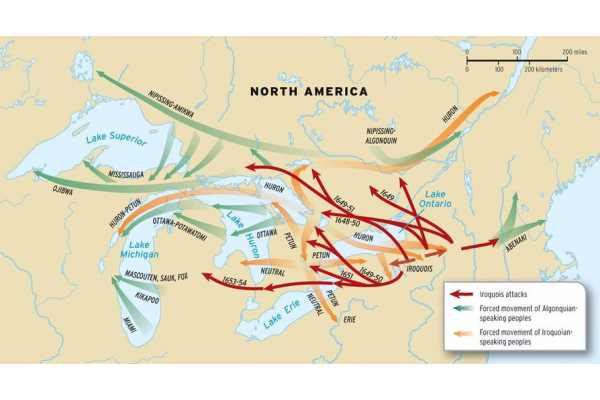

I. The Beaver Wars (1609-1701)

A century-long military conflict, The Beaver Wars was an intercolonial competition for economic dominance in the Great Lakes region between the British, Dutch and French colonists.

Like many inter-colonial wars, the opposing colonial belligerents of the Beaver Wars sought out strategic alliances with different segments of the Indigenous population, pitting tribes against one another for interests alien to them: The economic and colonial dominance of British, French, and Dutch slave-owners and mercantilists over Indigenous people, land, and resources. The Iriquois had aligned with the British and Dutch, whereas nearly twelve tribes aligned with the French, including the Wyandot, Algonquin, Erie, Ottawa, and others.

Although the outcome of the Beaver Wars is considered to have been indecisive, several Native tribes had been permanently impacted by the effects of the war, shifting the tribal geography of the region tremendously. The Iriquois would become dominant in a large portion of the region, gaining access in 1670 to the New England Frontier and the Ohio River Valley. The French colonists would also benefit from increased territorial and economic dominance of the region, until they were ultimately expelled from the region in 1763 following the French and Indian Wars.

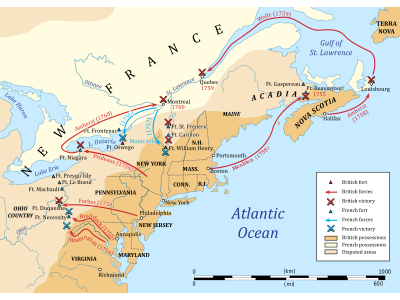

II. French and Indian Wars (1753-1763)

In the 1740’s, British and French colonists began to pivot their colonial aspirations towards the Ohio Country. The French and Indian Wars functioned as the North American front in the global conflict known as The Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). In 1749, the British Monarchy and the Virginia Colonial Government granted the Ohio Company access to the territory, ordering them to begin building settlements immediately. During this time, the French also made claim to ownership and control over the Ohio Country, leading to a clear and present inter-colonial conflict.

In addition to the growing competition between French and British colonists over control of Ohio Country, the Iroquois had laid claim to the territory since the end of the Beaver Wars.

After initially remaining neutral, the Indigenous tribes of Ohio Country- including the Shawnee- ended up aligning with the French, utilizing their weapons in raids against encroaching British settlers. After the Shawnee destroyed the Pennsylvania Militia’s Fort Granville in 1756, the Colonial Governor of Pennsylvania, John Penn, ordered a thorough and uncompromising military campaign against Shawnee villages West of the Alleghenies.

Through a series of successful military campaigns, the British colonists effectively drove the French out of the region. Following their defeat, the French signed the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ceded all territorial control of the Ohio Country to the British, without consulting their Indigenous allies who were Native to the region.

III. The Proclamation of 1763

Issued on behalf of King George III, the Proclamation of 1763 prohibited English colonists from moving West of the Appalachian mountains. The proclamation was issued to prevent imperial over-extension, avoiding unsustainable military expenditures and casualties. The 1763 proclamation was merely a provisional strategy which would provide time to the British military to recuperate following the French and Indian Wars, before they would re-commence their effort of colonial-settlement in Ohio Country thereafter.

The 1763 proclamation was a proximate cause for the breakout of the American Independence War nearly a decade later. Mercantilists, slave-owners, and settlers wanted to intensify and accelerate their colonial expansion westward, and felt that the British Monarchy was a fetter on their economic interests.

IV. Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763)

In 1763, a confederation of Indigenous tribes dissatisfied with British colonial-presence in the Great Lakes region launched a rebellion against the British colonialists in what is remembered as Pontiac’s Rebellion. Under the leadership of Pontiac of the Ottawa, the Indigenous confederation was able to successfully overrun eight British military bases, including killing and capturing hundreds of British colonists.

Although the Indigenous Confederaton’s military campaign against the British was ultimately unsuccessful in completely expelling the British colonists from the region, the rebellion did usher in a new period of anti-colonial resistance among the Indigenous tribes in the region, and the politics of unity among the Indigenous against their common colonial-oppressor was an inspiring example for a rising generation of anti-colonial revolutionaries.

V. The Battle of Point Pleasant (1774)

The only major action during Lord Dunmore’s War, the Battle of Point Pleasant was a battle between the Virginia Colonial Militia and the Shawnee and Mingo tribes. Under the leadership of Shawnee Chief Cornstalk, the Shawnee launched an attack on the Virginia Colonial Militia in an attempt to halt its advance into their territory in the Ohio River Valley. Unfortunately, after a militant and heroic battle, the Shawnee had to retreat. Pucksinwah, the father of Tecumseh, died during the assault.

After the battle, Chief Cornstalk signed The Treaty of Camp Charlotte with Virginia Colonial Governor, Lord Dumore. Among the mandates of the treaty, the Shawnee had to cede their territory South of the Ohio River (present day West Virginia and Kentucky), and to cease their assaults on settlers traveling down the Ohio River. Many Indigenous people disagreed with the treaty, and would continue to defend the land from further encroachment by settlers. Ultimately though, this treaty was torn apart at the onset of the American Independence War. The Shawnee and other Ohio Country tribes would use the war as an opportunity to widen their struggle against the settlers.

VI. The American Independence War (1775-1783)

Despite the limitations the British Monarchy placed on their colonies, such as the Proclamation of 1763, settlers from Pennsylvania and Virginia continued to push westward past the Allegheny mountains into the Ohio Country. Their push westward was met with Shawnee resistance at every step.

With the outbreak of the American Independence War, the Shawnee aligned with the British against the American colonists in the hopes of expelling the settlers permanently from the region.

VII. The Treaty of Paris (1783)

Following the resolution of the American Independence War, the 1783 Treaty of Paris ceded large portions of British “land” in North America to the newly formed United States, making way for a period of intense colonial expansion westward through the Northwest Territory toward the Mississippi River. The 1783 Treaty benefited both its British and U.S. signatories: allowing for U.S. mercantilists, slave-owners, and settlers to expedite their colonial conquest without the hesitations of the British Monarchy; while the British could benefit from a new trading partner in North America without having to expend money and military resources on defending the colonies.

More important than formal independence from the British Monarchy, the 1783 Treaty ceded the Northwest Territory- present day Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota - to the United States, laying the groundwork for their westward colonial conquest. The treaty also established the Great Lakes as a border between British and U.S. territory.

Known then as the Trans-Appalachian Settlement, the U.S. recognized the Northwest Territory as “unorganized territory”, building settlements immediately through the provision of land grants to veterans of the Continental Army. The Shawnee and other Native tribes of the Ohio Country continued to resist the encroachment of settlers on their lands, leading to the Northwest Indian Wars.

VIII. The Northwest Indian Wars (1785-1795)

By the conclusion of the American Independence War and the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the Ohio Country and Great Lakes region had been a battleground between European colonizers and Native tribes for over two centuries. From the intercolonial conflict among the Dutch, French, and British during the 17th century Beaver Wars, through the 18th century French and Indian Wars, Pontiac’s Rebellion, and the American Independence War: the Europeans’ settler-colonial project began to successfully expand past the Appalachian mountains, solidifying in the Ohio and Illinois Countries, and aimed further westward towards the Mississippi River.

This was a pivotal moment for the Native tribes of the region to mount an effective counter-offensive against the imminent development of settler-colonialism by the newly formed slavocracy East of them- the United States. In response to the settlers’ expansion West of the Appalachian mountains, a Huron-led confederacy of Native tribes formed in 1785 to resist the U.S. government. Known as the United Indian Nations or the Western Confederacy, the Native Confederacy declared all land North and West of the Ohio River as Indigenous territory — any European settlement within the region would be met with nothing less than armed resistance.

In retaliation to the Native Confederacy’s claims to sovereignty over the region, George Washington and the U.S. Army launched a military campaign against the insurgent Indigenous revolutionaries. During the initial phases of the campaigns, the U.S. Army suffered a number of defeats. At the Battle of Wabash River (1791), over 1,000 Miami, Shawnee, and Delaware warriors launched an assault on the U.S. occupation force. Of the nearly 1,000 U.S. soldiers who were stationed on the river, only 24 survived. It is regarded as the greatest military defeat in U.S. history, as well as its greatest defeat by Native anti-colonial resistance.

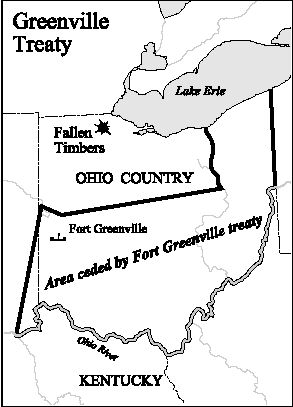

However, after their defeat at the Wabash River, Washington and the U.S. Army adjusted their military strategy, until ultimately solidifying their victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794) and formalizing their land-grabs with the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

IX. The Treaty of Greenville (1795)

Following their defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers a year earlier, the United Indian Nations signed the Treaty of Greenville which effectively ended the Northwest Indian Wars in the Ohio Country. The treaty dispossessed all Native Ohio Country tribes to the Northwest corner of Ohio and mandated that the tribes pay tribute to the U.S. government annually. The Treaty initiated a turning point in the Trans-Appalachian Settlement colonial-project, soon ushering the state of “Ohio” into the U.S. 's claimed sovereignty in 1803.

Conclusion

The above historical sketch is by no means complete, nor should it be considered as the final word on the development of settler-colonialism in Ohio. Over the two decades following the Treaty of Greenville, the U.S. government would seize- through a series of colonial decrees and raids- the rest of the Ohio Country: wresting the land away and dispossessing the remaining Indigenous tribes. In the case of the Shawnee, many would migrate West to Missouri and Kansas, until being dispossessed again, this time to Oklahoma where many remain today. Today, there are no federally-recognized tribes in Ohio, and the Indigenous population of Ohio is 0.3%.

The history outlined above was needed to set the stage for the entrance of Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, and the militant anti-colonial, pan-tribal response they would spearhead at the turn of the 19th century. Part two of this essay will focus on Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, offering an appraisal for their politics and philosophy, and shining a light on their significance for revolutionaries today.